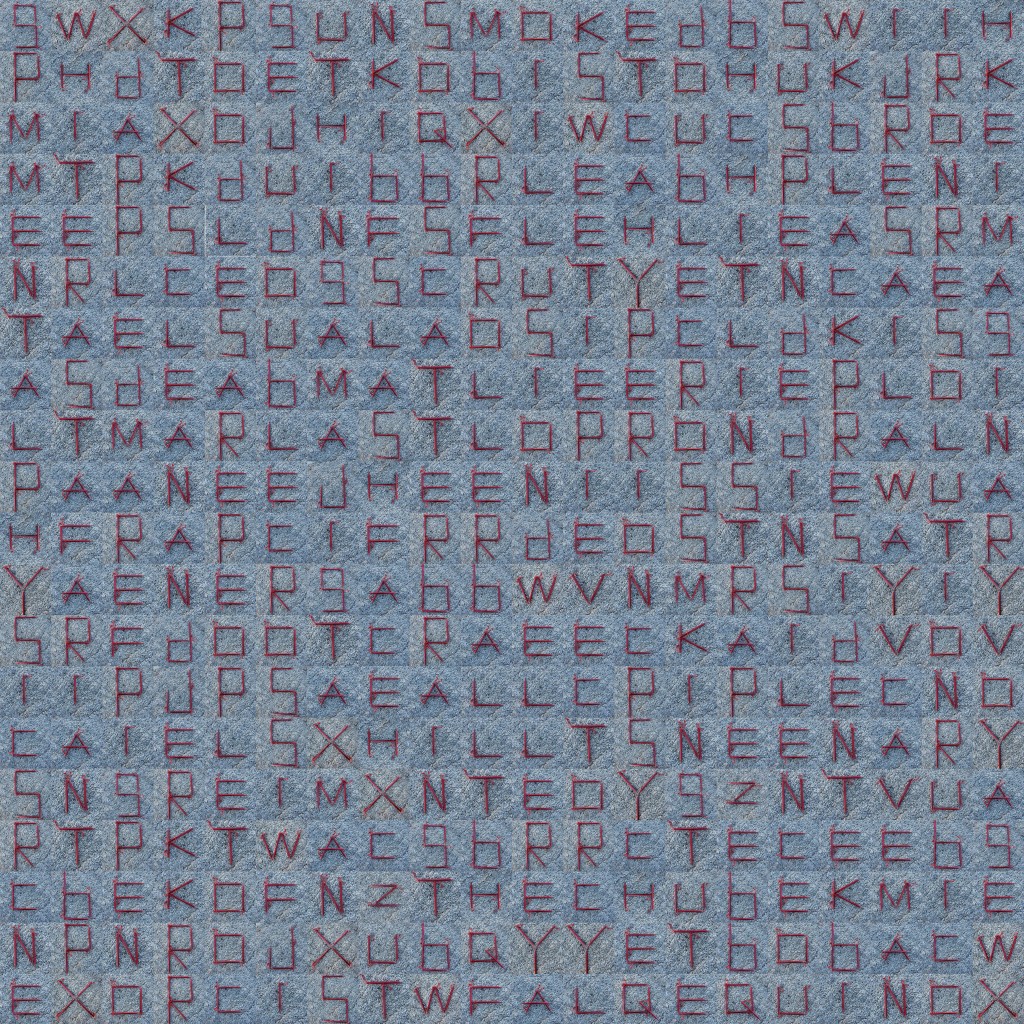

'The Rocks' is a ground-based installation that invites audiences to consider the way in which they read and mark landscapes. Alphabets formed from tent pegs are arranged and photographed in different conditions and used to form hidden texts. In the manner of a word search puzzle, the audience is encouraged to discover words within the work that provoke thought around the territorialisation, custodianship, and temporality of the land.

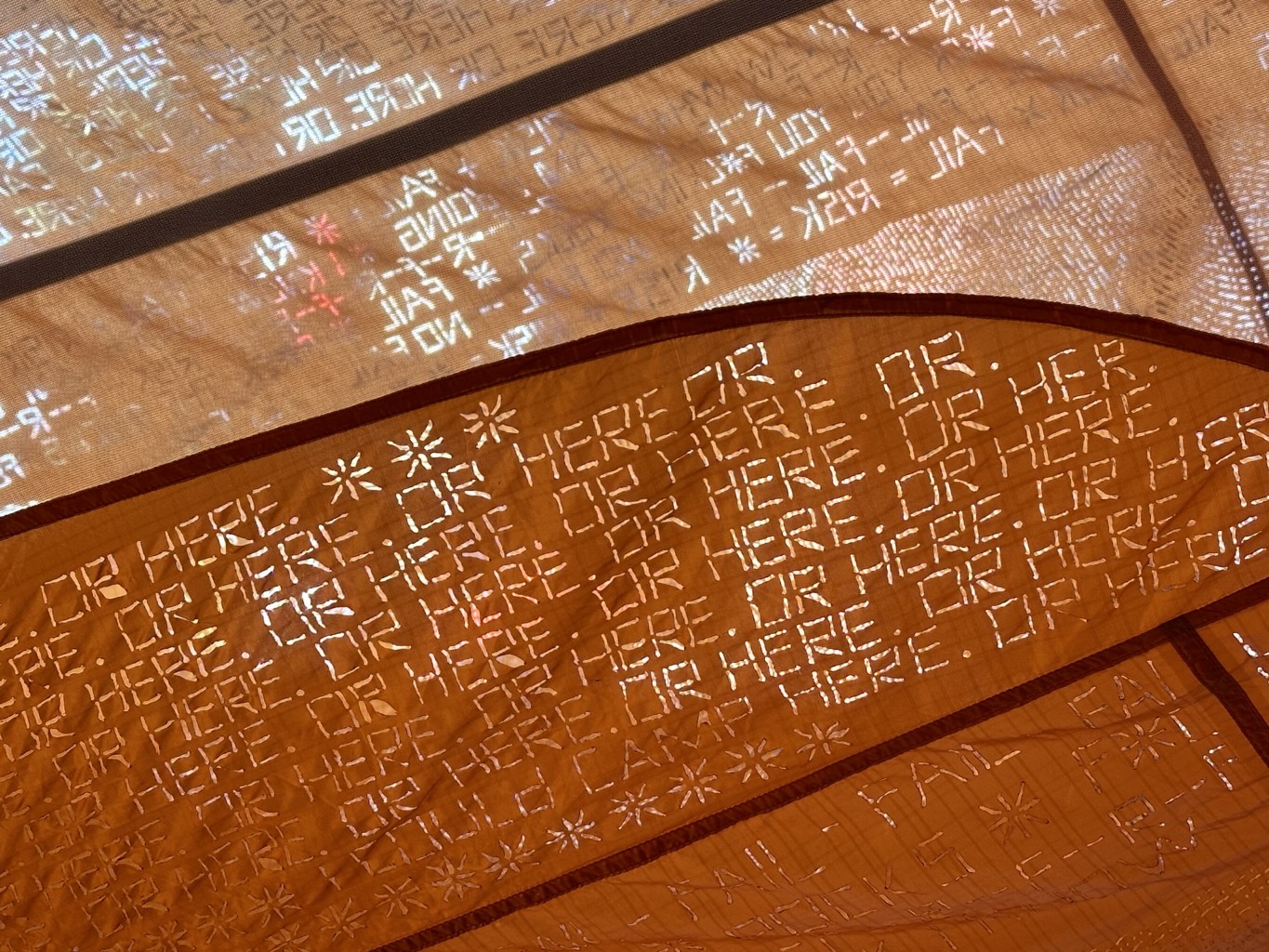

Copper Spur is a meditation on architectural transience in an extreme landscape. It was displayed at the European Cultural Centre in Venice, Italy, as part of the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennial. In this work, a Copper Spur tent that was carried on the Larapinta Trail in the Tjoritja West MacDonnell Ranges in central Australia is presented as a ritualized itinerant architecture. The Copper Spur was repetitiously unpacked, constructed, inhabited, deconstructed and re-packed on a daily basis over several weeks. It was a companion for the solo walker, cared for and carried over a long distance; a suggestive space that listened, spoke, recorded and constantly co-created place with its mobile inhabitant.

After its journey, the fabric floor of the tent now registers the landscape as a series of intense contact points that have been burnt into its surface. Key moments of compression – the foot upon the path and the camp upon the earth amid the deep time of geology – are registered as disappearances that vanish into an elsewhere of irreversible change. Only the imagination of a tiny wisp of smoke from each perforation exists to recall the intense and enigmatic exchange of body, earth and architecture.

This work was a floor-based temporal installation that grew from a quiet obsession with the ceiling in the Australia Square foyer. The ceiling was understood as a repetitious pattern of solid and void. The installation questioned the stark solid-void duality and investigated the invisible or barely-perceived physical matter that occupies the void spaces. The voids were reconsidered as positive volumes that have the capacity to cast a ‘shadow’ upon the floor. Fine particulate matter, a tangible physical component of air and a standard indicator of air quality, was captured and arranged on the floor plane in an intricate geometric pattern that placed the floor in direct visual dialogue with the ceiling.

The installation was comprised of two parts separated by external glass wall – one part was inside the foyer, and the other part continued outside. Inside, the voids of the ceiling grid were referenced on the floor using areas of finely crushed glass arranged directly on the floor. The crushed glass is considered as particulate matter, a luminous representation of the invisible suspended matter of the air. Outside, the solids of the ceiling grid were hand cut out of water-soluble embroidery film to form a geometric ‘web’, which was interspersed with areas of black silica. During the evening, performers and the audience sprayed a fine mist of water on the film, slowly dissolving the work until it disappeared completely. In this work, solid and void were inverted, reversed and imaginatively multiplied across the horizontal planes of the building.

This work explores the intersection of art, architecture and landscape and is part of a sequence of bespoke spaces that respond to the specific conditions of a garden site. This iteration is made especially for small children.

A jewel-like space of colour and delight is positioned within the garden to function as a hideout, cubby, and retreat. Visitors sit within the space and quietly absorb the kaleidoscopic effects of colour and pattern in relation to the surrounding landscape.

House for a Lost Tree focuses on pattern-making and is influenced by the forms and structures of the natural world. The flexible leaf-like cladding rhythmically overlaps to mix colours and generate rich geometries to produce an immersive, atmospheric and contemplative space in the landscape.

Eden Garden, Sydney; birch plywood, blackbutt, polypropylene, steel; approx. 2m diameter, 2.5m high.

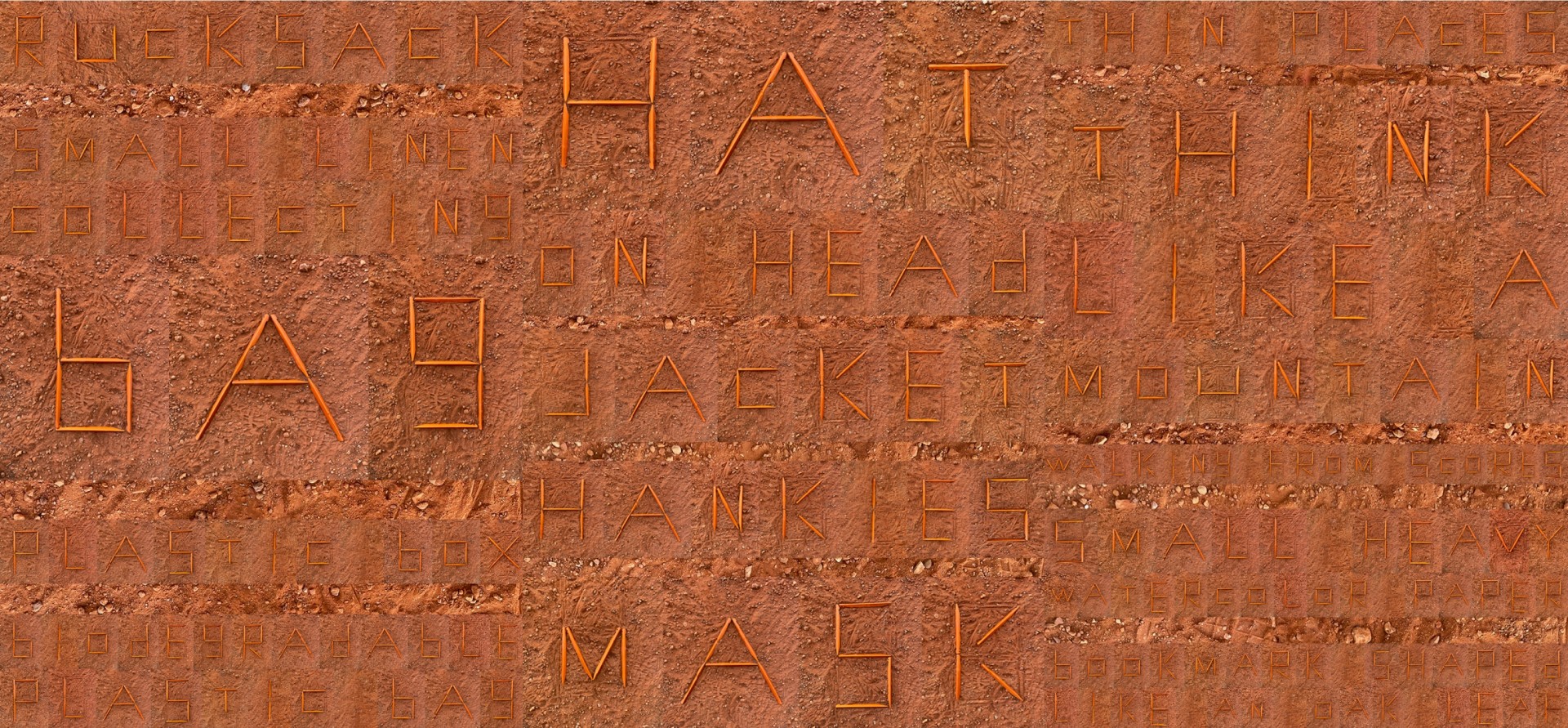

Crit-i-kit is a game that explores the tools, equipment and supplies that are considered ‘essential’ to the inhabitation of landscape. Walkers encountered by the artist in a variety of environments anonymously shared the complete contents of the bags they were carrying at the time; items were then catalogued and grouped into broad thematic categories. Each category is printed onto a card that is then randomly selected by a player and used to guide a new walk.

This work prompts consideration of the structures we individually build and respond to as we walk within the world. Each item is proposed as a structure that guides our inhabitation; a vessel for carrying, a gesture of care, or an item of potential are each thought of as prompts for spontaneous architectures that result in profoundly different modes of living.

This work is supported by the NSW Government through Create NSW and the School of Built Environment at UNSW Sydney.

In November 2024, I was the Joshua Tree National Park Artist in Residence. I made a series of campground drawings called Campground Cutouts and a series of wordsearch works called Desert Problems. Campground Cutouts interpret some of the 600 campsites within the park. Desert Problems invite viewers to locate bouldering routes within a photographically constructed geological landscape and consider their curious nomenclature.

The Registry of Itinerant Architectures is an interactive online archive that records encounters with wild, mobile, fleeting and unlikely structures in varied geographic, social, cultural and political settings. It exists on the edge of interdisciplinary art and architecture practice, resisting and disrupting the conventions of architectural experience and record-keeping. The Registry incorporates a dynamic mix of moving image, text and artefact, brought together in an open-access online environment that is available for instant and ongoing global dissemination.

The Registry of Itinerant Architectures is developed by the mobile artist — the Registrar —who walks or moves with mobile communities and repeatedly attempts to apprehend forms of itinerant architecture through observation, imagination, narrative and memory. In doing so, the Registry of Itinerant Architectures poses a twinned question: is this architecture, and who is the architect?

Forms of itinerant architectures may include mobile natural and built architectures, fleeting and invisible structures, condensations and sedimentations, weather events. This is a playful artistic practice that is mobile itself precisely as it investigates other mobilities; the Registry moves with and creates itinerant space with its subjects. Evidence of itinerant architectures is published at www.itinerant.academy to formulate a steady and cumulative body of work. A global audience considers each work as a proposition and then accepts it or rejects it, actively co-creating the Registry over time.

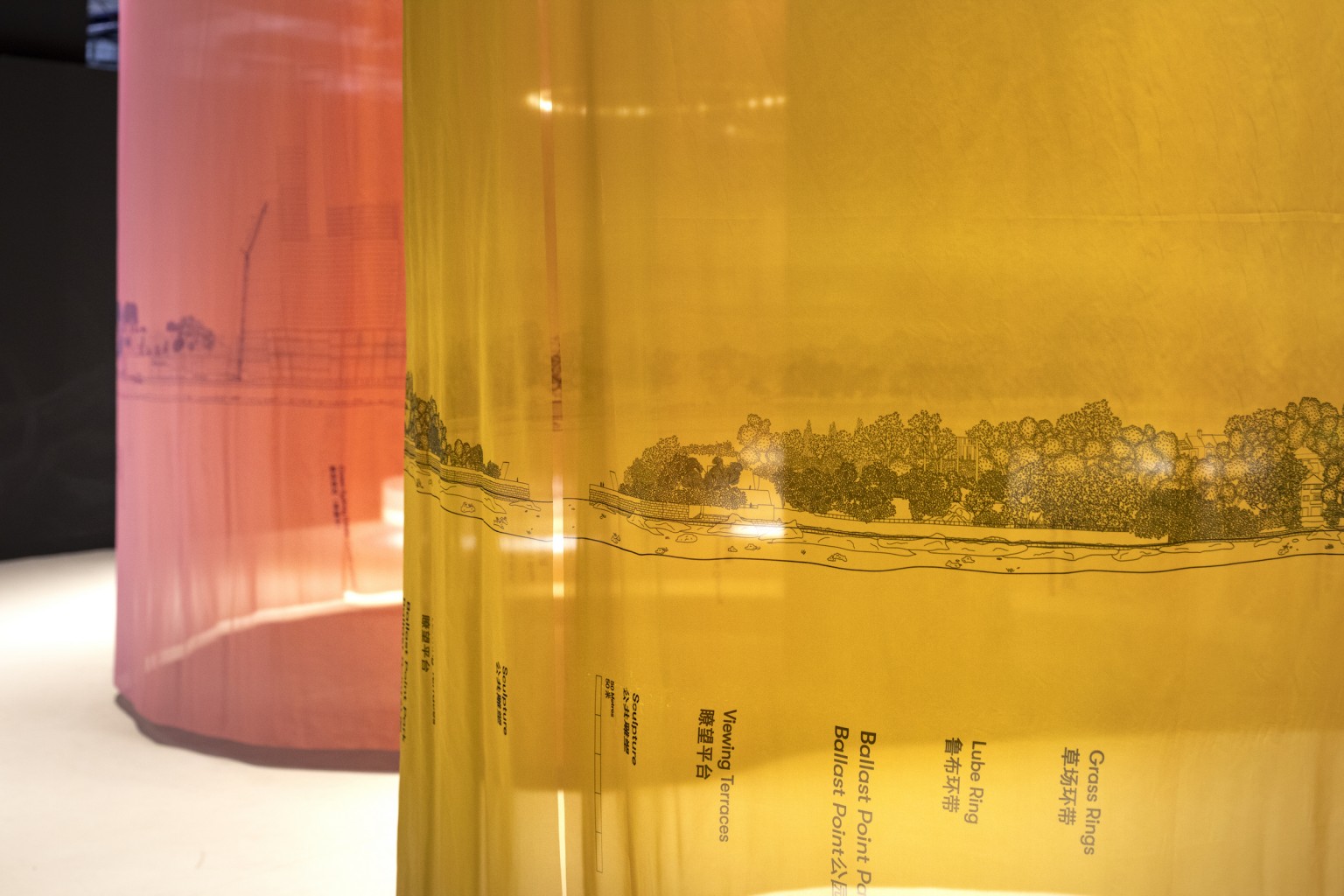

Aqueous Landscapes is an exhibition that explores the complexity and nuances of the constructed edge of Sydney Harbour, showing how the foreshore is used and experienced on both land and water. The exhibition is shaped by a monumental textile drawing, Unravelled Foreshore #1, that evokes the bays and inlets of a harbour journey as it curves through space. The drawing depicts an unfolded view of the Sydney Harbour foreshore over 45 metres, and undulates across multiple scales to reveal in detail the character of life in these distinctive public spaces. This drawing, developed from a photographic survey conducted by boat, captures the contemporary architectural, cultural and environmental conditions of Sydney Harbour at the rich interface of land and water. A short film, Intertidal Sections, also features in the exhibition. Imagery of water, edge and sky is spliced and then multiplied to reflect the material, ecological and atmospheric diversity of the Sydney Harbour. Aqueous Lanscapes was co-curated with Helen Lochhead, designed by Trigger Design and produced with Joshua Sleight.

With landscape architect Joshua Zeunert and artist Cathe Stack operating as A. W. E. collective, we curated a special edition of Powerhouse Late: Landscapes on April 20, 2023. The event was an elemental-themed exploration of our cultural relationships with landscapes, and featured an immersive museum experience. The audience were offered walking sticks to guide them through the museum; the sticks were collected from Bundanon Art Museum and then frozen by the Powerhouse conservation team prior to distribution.

The program included:

River : Jennifer Peedom & Joseph Nizeti

Phantom Ride : Daniel Crooks

Wattie & Wheatbelt Anticipatory Archive : Perdita Phillips

Sonus Maris : Nigel Helyer & UNSW New Music Collective

Wall drawing & music place-scapes : Sarah Jane Moore & Michael Galeazzi

Performance : The Sleep Walkers

Feral Atlas : Anna Tsing, Jennifer Deger, Alder Keleman Saxena & Feifei Zhou https://feralatlas.org/

Glass Gardens : UNSW New Music Collective https://www.theglassgardens.com/

Band : Manfredo Lament

Moondance holds the slow choreography of an extended mountain walk in Banff National Park. This itinerant architecture was repetitiously carried, unpacked, constructed, inhabited, deconstructed and re-packed over several days and nights, operating as both refuge and companion to the solo walker. En route, each interaction was a gesture of ecological and material correspondence; in the studio, iterative mark-making transformed memory into meditative texts and imaginative trajectories. Later, suspended in the forest and illuminated in the early morning light, it hovered as a drawing of air and of attention – a shimmering inquiry into the ethics of inhabitation.

Two rafts were walked along the tideline from Queenscliff to Shelley as part of the Manly Arts Festival.

These are rafts.They are made from bird spikes.

The bird spikes are sold as a ‘humane’ form of species control.

We install bird spikes on building ledges, signs and lights to prevent birds from landing.

Though beguiling in gleam and form, they embody an unthinkable hostility toward the other.

The assumption of the right of aggression toward another species insulates us from grasping the aggression of these objects.

Look to the bird that flies past you just now and to the person who stands quietly beside you.